Informal, Exploratory Writing Activities

Informal exploratory writing, when assigned regularly, can lead students to develop insightful, critical, and creative thinking. Experience tells us that without this prompted activity, students might not otherwise give themselves enough time and space to reflect on class content, or to forge connections that will allow them to remember and use ideas from assigned readings, lectures, and other projects. These brief writing activities also allow instructors to get a general sense of students’ grasp of course concepts and materials, and can, in turn, inform future lecture notes, class plans, and pacing. The activities listed below can take as little as 5 minutes of class time.

Freewriting

Freewriting, a form of automatic writing or brainstorming promoted by writing theorist Peter Elbow, requires students to outrun their editorial anxieties by writing without stopping to edit, daydream, or even ponder. In this technique, all associated ideas are allowed space on the page as soon as they occur in the mind. Five-minute bouts of freewriting can be useful before class to spark discussion; in the middle of class to reinvigorate, recapitulate, or question; and at the end of class to summarize. It is also useful at many points in the drafting process: during the invention stage as students sift for topics, and during the drafting process as they work to develop, position, or deepen their own ideas.

Two types of freewriting assignments have been used in courses across the disciplines: prompted and open. Prompted freewrites allow students opportunities to initiate or develop their thinking on a topical, instructor-supplied prompt, for example, “What is a virus?” Open freewrites, on the other hand, allow students to simply write in order to clear their minds and orient themselves to a class session. Using either form, students are directed to write continuously for a set amount of time. If they get stuck, they can write generic phrases like “I can’t think of anything to say, I can’t think of…” or “Nothing nothing nothing..” until ideas come to them and they can jot them down.

It’s a good idea, particularly in the case of prompted freewrites, for students to take a few moments after the timer has gone off to read over what they’ve written, highlighting useful and interesting ideas that may be glittering from amidst the verbal rubble (see example below). These insights might then be used for a next round of prompted freewrites (this practice is called looping) or developed into content relevant for a more formal writing assignment. At the very least, highlighted or underlined ideas can provide students with ideas they can contribute to class discussion.

Note that freewriting is often personal and messy. If it is intended as a low-stakes and formative writing activity for students, one in which ideas can emerge in an unedited flow, you’ll likely want to refrain from collecting it and will want to make this choice clear to students from the outset. For ideas about what can be done with the informal writing students do, see Responding to Informal Writing.

Five-minute papers

Five-minute papers are a variant of prompted freewrite and of the informal assessment strategy called the Minute Paper. The primary purpose of five-minute papers is to provide opportunities for students to increase their familiarity with course-relevant thinking and writing abilities and the primary audience for these low-stakes writing activities is the writer.

Five-minute papers can be completed on a scrap of paper, index card, tablet, etc.; at the start, middle, or end of a class; and whether you’re teaching a large-format lecture, an intimate seminar, or a technical lab or studio. They provide a targeted and low-stress opportunity for students to develop precisely the sorts of thinking abilities we hope to see demonstrated in larger, higher-stakes assignments. Here they can generate, summarize, question, reiterate, propose, defend, synthesize, or apply ideas. Such writing helps students to digest, apply, and challenge ideas and can help them achieve enough confidence to apply similar abilities in next-stage assignments and contribute fruitfully to class discussions. These short writing assignments also deliver quick, valuable feedback to instructors on what students are learning.

Note that timed and cognitively focused writing can be stressful for some students. You may want to negotiate alternative approaches for some students. These may include making the writing prompts available to some students in advance of class. Doing so will allow them to arrive with their ideas already in hand and ready to discuss. Consider consulting with the Disability Resource Center for more on this.

The following are examples of prompts:

Any Discipline

Prompt: Create a bumper sticker that would summarize yesterday’s lecture.

Target thinking ability: Distillation of complex ideas

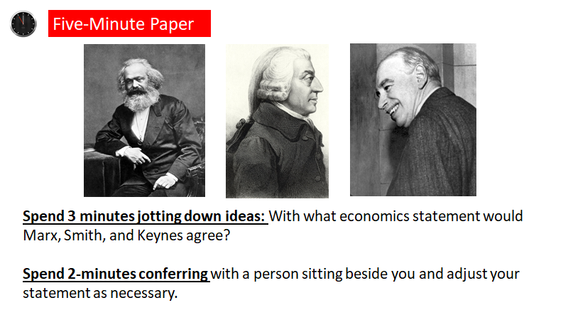

Economics

Prompt: Take 5 minutes to write a statement with which Marx, Smith, and Keynes would agree.

Target thinking ability: Synthesis

Sociology

Prompt: Generate a list of research questions prompted by the recent Black Lives Matters demonstration (3 minutes). In triads, compare lists and select/revise one question that would be workable for a 6–8-page research paper.

Target thinking ability: Posing viable and appropriately scaled research questions

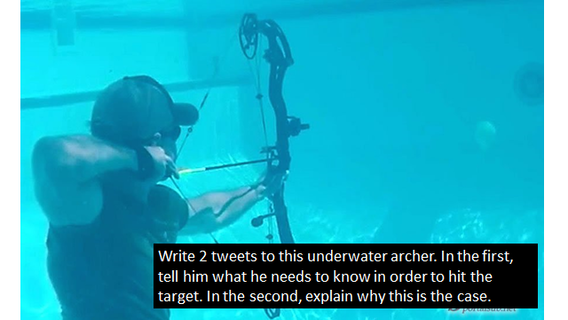

Physics

Prompt: Write two tweets to this underwater archer. In the first, tell him what he needs to know in order to hit the target. In the second, explain why this is the case.

Target thinking ability: Enhance understanding of difficult concept