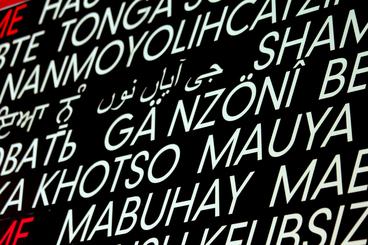

Supporting Multilingual Learners

The University of Minnesota thrives on a linguistically diverse community of native-born, refugee, resident, and international students. We use the term “multilingual writers” to describe University of Minnesota students who speak and write in English, though English is not their primary language. Like writers who are native to English, multilingual writers continue to develop written fluency as they move forward in their majors and chosen fields. Unlike native writers, though, some multilingual writers may retain (by habit or choice) features of their native or preferred languages in their English writing. These students may approach courses and writing assignments from a variety of cultural perspectives and belief systems that are worth consideration.

In a position statement related to second-language writers, the National Council of Teachers of English reminds us that “beliefs related to individuality versus collectivity, ownership of text and ideas, student versus teacher roles, revision, structure, the meaning of different rhetorical moves, writer and reader responsibility, and the roles of research and inquiry all impact how student writers shape their texts.”

Prioritizing Issues

Some instructors may find the prospect of working with multilingual writers challenging because some of the issues detected in these students’ writing can be difficult to decipher and prioritize. Some writing challenges are shared with other undergraduate writers (e.g. thesis, focus, organization, use of evidence), regardless of their language of origin, and some may be particular to specific linguistic traditions and backgrounds. Some issues may also arise from variations in educational and cultural practices that do not align with the instructor’s expectations or with conventions associated with North American academic writing. To avoid overwhelming multilingual writers and themselves, instructors can prioritize their teaching and assessment strategies by aligning them with specific stages of writing.

Getting a sense of who’s enrolled in your course

Before you distribute (or unlock) writing assignments, it can be useful to get a sense of students’ familiarity with and proficiency with the kinds of writing you’ll be expecting them to do in a course. Getting early-semester samples of writing from all students can help you to avoid making unwarranted assumptions about writing abilities based on names, progress to degree, majors, etc. These early-semester assignments can answer student questions: What kind of writing will I be doing in this class? How does writing in this class compare to writing I’ve done in other classes? Am I prepared to do this? These assignments also answer instructor questions: How familiar are students with the kinds of writing I expect them to do this semester? What sorts of pacing, intervention, and provision of resources should I be considering?

As you’re creating a writing assignment

Consider cultural assumptions embedded in writing assignments. Try reading through a writing assignment from the perspective of a multilingual student. See any cultural references (e.g., references to American history, pop culture, or media) that may not be meaningful to some students? Any idiomatic expressions that may trip these students up? In either case, you might want to eliminate, footnote, or hyperlink them to explanatory sources.

Discuss and clarify the expectations for the writing assignment at the outset. Along with designing clear and transparent writing assignments, instructors can explain in concrete terms the vocabulary they use to respond to and assess student writing. Terms like “thesis statement” and “supporting evidence” often have different meanings and applications, depending on one’s educational background. For example, the absence of a direct thesis statement in the opening paragraph—often valued in North American academic discourse—might be the result of different expectations about how to structure an argument and different rhetorical approaches. Developing clear and concrete grading criteria that describe strong thesis statements, effective use of evidence, etc., can be particularly useful in underscoring expectations.

Present writing assignments in multiple modes—verbal, oral, visual, graphic. Research that draws on Universal Design for Learning principles and practices has shown that assignments presented in multiple formats can reduce barriers and increase access for all students, especially multilingual learners.

Provide annotated models of effective writing for the assignment. Sample excerpts that exhibit desired valued writing features can underscore writing expectations while also demonstrating the range of responses that can encompass student work. Research in the field of applied linguistics has helped to identify how the rhetorical styles students bring to the classroom are strongly shaped by cultural and educational backgrounds and the models they have been exposed to. As Helen Fox points out, “the dominant communication style of the U.S. university” is considered “sophisticated, intelligent, and efficient by only a tiny fraction of the world’s people” (quoted in Bean, 85). Models can be very effective in helping multilingual learners become familiar with new rhetorical norms.

As students are completing a writing assignment

Provide direct and instructive comments on drafts. In many instances, prescriptive commenting can seem overly controlling. However, for some multilingual learners, directive comments can be effective for aligning a linguistic practice with specific genres, conventions, or disciplinary practices. For example, an instructor might write, "You need a thesis statement at the beginning of this paper." Likewise, the instructor might find a thesis statement later in the paper and tell the student where academic audiences in the United States would expect to find it. Framing prescriptive feedback comments in terms of North American audience expectations can convey writing values while avoiding a critique of other linguistic and cultural practices and traditions.

Focus first on content and organization before grammar. Grammar issues and errors can mask more important concerns for multilingual writers. Focusing first on grammar may also mask or minimize the successful points of the paper and cause instructors to overlook disciplinary strengths and insights presented in the writing. Some effective commenting strategies used by instructors who work frequently with multilingual writers include:

- Reading through the entire draft before commenting. This allows you to read first for ideas and to make choices about high-profile issues that merit comments.

- Providing written comments about organization and ideas and commenting on patterns of errors.

- Asking students to hand in another draft for grammar comments after the ideas are more developed and organized.

- Focusing selectively on grammar issues and providing a rule that can help the student fix the issue. Read more about commenting on grammar, usage, and mechanics.

- Selectively correcting only those grammar issues, such as articles, prepositions, word choice or idiomatic expressions for which there are few rules or patterns.

- Suggesting that students work with a multilingual writing specialist in Student Writing Support and that they utilize the Center for Writing’s online resources.

At the end of the writing assignment

Although many instructors learn by trial and error how best to support multilingual students, grading is still a confusing task. A recurring question for instructors is how they should grade the writing of multilingual students fairly when the paper still has grammar errors. Here are several approaches that can work for instructors.

- Categorize and weight what you are grading. Try using a written checklist or rubric that categorizes several areas such as organization, critical thought, narrowed thesis, and grammar with the heaviest weight of the grade being critical thought and organization. Less weight can be given to categories such as grammar and sentence structure. In this way, if the student has very good organization and ideas, they are given credit in those categories, but they are graded down for sentence structure only in one area. This helps the student realize that the paper has several aspects that are worth looking at. Most instructors using this method will grade down only on areas that interfere with understanding of thoughts. Minor problems such as subject-verb agreement, article usage, etc., are usually overlooked or viewed as features of multilingual writing.

- Grade primarily on content, but circle types of errors on the final draft and ask the student to correct and hand in an edited copy once the ideas are clear (or at least graded). Some instructors also align this approach with the use of error logs. Research has shown that indirect feedback identifying errors with a circle or a check mark can help students become stronger self-editors of their writing.

- Require students to hand in final drafts for a grade on the due date, which does not include any penalty from grammar errors. When the paper is handed back, the student may take the paper to a writing center to work with a tutor—not to 'perfect' the paper or create an error-free version, but to learn more about finding and editing these errors. Research has suggested that when students revise after correction, their accuracy improves over time.

Additional Considerations and Resources

Instructors may wonder about the effects that their support for multilingual writers has beyond an assignment and beyond their course. One question that has been rigorously researched is whether error correction helps multilingual writers develop accuracy over time. Is it worth it to address writing errors? Summarizing this research, Dana R. Ferris concludes that indirect feedback, which typically requires less time than direct proofreading, has “greater potential long-term benefits for students improvement in accuracy because it provides students with the feedback they need to engage in problem solving and move toward becoming ‘independent self-editors’”(65).

The University of Minnesota has a number of resources for instructors working with multilingual learners. We encourage you to explore and bookmark these valuable sources of support:

- Student Writing Support (SWS) features Student Writing Consultants who specialize in working with multilingual writers. SWS also provides online guides and resources for multilingual students.

- Writing for International Students (WINS) provides strategies for supporting multilingual learners as they negotiate the academic and social demands of a United States university system.

- Student English Language Support (SELS) also offers one-on-one consultations for multilingual learners that cover a range of topics, including comprehension skills, vocabulary, and grammar.