Commenting on Student Writing

Commenting on student writing is among the most important tasks for any instructor who uses writing. Whether the writing is short or long, formal or informal, a work-in-process or finished product, students learn both course content and writing habits through the process of revising their own writing.

Focused written feedback is the most effective way to promote students’ continued development as writers and learners. The function of commentary is to ask students to think about and consider their choices as writers and to promote a dialogue between student writers and their instructor/readers. When instructor comments are successful, students report that these opportunities for dialogue are influential on their learning and motivation.

Comments can include marginal notes on a paper document, an endnote paragraph, comments and changes using review tools in a word processing application, audio and video commentaries, or the conversation with a student in a one-to-one conference. Unlike grading, commenting on student writing can happen at any time in the writing process. In fact, earlier formative feedback is most likely to lead to revision and improved student performance (whether from peers, teaching assistants or primary instructors). (Graham et al. 2011) By contrast, providing summative feedback early in the writing process—such as assigning a grade to a preliminary draft—can have demotivating effects on student writing. (Mizak)

- Ways to comment on student writing

- What types of comments should I use?

- Guidelines for effective commentary

- Commenting on sentence-level errors

- Audio and video feedback

Ways to comment on student writing

When asked about what they prefer from faculty comments on writing, students most often mention detail and specificity. Given the time pressures on faculty and instructors, how might we meet this demand without spending hours on each student draft?

Not all comments are created equal, and different contexts might demand different strategies for commentary. This list identifies a variety of strategies of commentary and provides examples from four concrete assignment contexts.

Open-ended questions: In the early stages of a draft, open-ended questions provide students with indications of a reader’s reaction and can encourage writers to tailor their written work to audience needs and add detail and specificity. Open-ended questions should prompt ideas and additional consideration of a topic, and should not point to an easy or obvious answer.

Examples:

How do examples of conflict in other relational contexts (like workplaces, parent relationships, or sibling relationships) differ from conflicts between intimate partners?

How did you manage the functional requirements of this garment’s sleeves with aesthetic considerations?

Why might opponents of excise taxes also be critical of state-run lotteries and gaming?

Given the reaction you observed in this context, what effects would you expect oxygenation to have on other organometallic compounds?

Coaching: Coaching comments typically isolate a particular feature of a text and offer recommendations or suggestions for revision. A coaching comment often combines a statement of observation with a recommendation for another iteration or attempt.

Examples:

You make an important connection here between the intersections of power and authority in social relationships and the dynamics of relational conflict. You could develop this argument as part of the larger argument.

You’ve picked up on the common term “sin tax” to describe excise taxes on items considered to be luxury items. How might you distinguish these from excise taxes on necessary items (like food or medicine)?

Praise: Effective praise combines two facets: noticing something praiseworthy about the text and describing what makes it a successful attempt. The goal of praise is both to affirm effort and to encourage the repetition of the successful choice. Praise that lacks specificity (such as good job! Or This is key!) may not provide enough information to students to help promote effective writing strategies.

Examples:

I really appreciate your choice to vary the textile on your sleeve as you describe the project. Not only does it offer greater freedom of movement, but it also adds visual interest.

This figure is great. The title describes the important findings that it represents rather than simply restating the variables under consideration.

Explanation or clarification: Explanation or clarification comments typically identify an error, misconception, or incomplete understanding in a student’s writing and provide correct or complete information. If you notice a student has a misconception or is making an analytical error, an explanation provides additional information or reiterates an important point from instruction. Explanations and clarifications typically identify an error or omission and furnish a better alternative.

Examples:

Remember that “intimate partner” can describe both persons currently engaged in a romantic relationship and the relationships between people who have suspended or ended their relationship. Thus, conflicts with ex-spouses can still be considered intimate-partner conflicts even if they no longer cohabitate.

It’s worth noting that while vendors collect excise taxes, the collection of taxes is actually an added expense for retailers and wholesalers. They are acting as agents of the government when they collect taxes and have to expend time and resources to transfer payment, but they don’t receive direct compensation for that work.

Closed-ended questions: Closed-ended questions often demand a specific answer. Close ended questions often solicit specific information that has been omitted, and students will often consider a simple answer as sufficient.

Examples:

Is the outer shell of the garment connected to the lining with adhesive?

What was the yield of the reaction?

Criticism: Criticism typically identifies a flaw or weakness related to a textual feature. Much like praise, effective criticism usually identifies and describes a noteworthy textual feature and explains the challenge, issue, or problem associated with it. Criticism that lacks specificity (such as “this section needs revision) does not supply enough information for students to revise strategically.

Examples:

In your description of intimate-partner conflict, you often refer to “the man” and “the woman.” It’s important to remember that while gender is a salient feature of intimate partner conflict, we should not presume that the behaviors you describe are necessarily connected to gender expression.

In this paragraph, you use “sales tax” as a synonym for excise tax. While excise taxes are associated with the sale of particular goods, sales tax can apply to any purchase. Thus, a local option sales tax that applies to all transactions would not be an excise tax.

Commands: Commands are comments that demand a student make changes to a text. They might address sentence-level features, elements of document format, or larger issues or concerns. Students may revise in response to commands, but may not know why such revisions are prudent or necessary. Note: some close-ended questions are simply commands in disguise. When a student is instructed to make a change through a command, they will often comply, but rarely will this lead to a change in subsequent writing.

Examples:

Indent your block quotation.

Cite this source using APA format.

Move this paragraph to the top.

Corrections: Corrections are changes a reader or assessor makes in a text. This often occurs with sentence-level errors, issues of style and word choice, but can also apply when a reader crosses out or removes sentences. Unlike a criticism, which identifies and explains a troublesome feature of a text, or a command that requires students to comply with an assessor’s directive, a correction eliminates it without any intervention from the student. While students may make changes based on corrections or accept corrections recorded in track changes, they are not revising their own writing.

What types of comments should I use?

For formative feedback, the most effective strategies to encourage student revision include open-ended questions, specific praise, and coaching. Open-ended questions provide meaningful opportunities for students to think more deeply. Specific praise promotes the features of good writing in your field and encourages good choices in the future. Coaching involves offering recommendations for a change of technique along with a justification for the change.

Where and how instructors comment has profound effects on students’ decisions to revise. In general, an endnote comment will address overarching issues in a document and will help a student writer set priorities for revision. These can often be organized as a letter to a student describing what is going well and how a student might make additions or changes to improve their writing. Comments in the margins of student writing (or comments added using a word processing ‘Comment’ feature) typically identify the precise location of an issue, problem, or opportunity for revision. When using commenting or track changes in a word processor, the presence of many marginal comments can make it hard to focus on crucial issues and to set priorities.

The closer the document is to its end stage, the more likely an instructor will use commands and corrections in the manner of a copy editor. Comments of these types emphasize perfecting and polishing the final product, not offering students an opportunity to reconsider their own work. It may be that after providing multiple opportunities for earlier learning, commands and corrections can help a student meet conventions of written discourse.

Guidelines for effective commentary

Limit the number of comments you make. Emphasize the priorities that are the most important to the student’s learning. It may help to focus a commenting session by referring to the assignment’s objectives or grading criteria. Even in cases where you encounter numerous problems, students perform more effective revision when the feedback is not overwhelming.

Spread writing activity over numerous assignments. Working through a sequence of shorter assignments (and sets of comments) provides students with opportunities to improve their writing, and allows you to return papers faster. A little bit of formative feedback and a short endnote will often be more effective than a long endnote on a single assignment.

Ask students to reflect on their work. As a writer, you are often aware of what you could do to improve a draft, but you just haven’t done it yet. Asking students to attach answers to these questions can save time: What is your purpose in this paper? What do you know you need to revise? Where would you like me to focus my reading and response?

Provide structured opportunities for peers to respond to drafts before you see them. For more information, see the Benefits of Peer Response page.

Respond digitally. You may find that you can say more—and say it more clearly and efficiently—if you use digital tools to respond (e.g. sending text by email, creating a Word document, sharing a Google Doc, recording spoken comments or a video response).

Commenting on sentence-level errors

It is important to distinguish commenting on errors from correcting errors: A comment on an error makes the writer aware of a potentially troublesome feature of a sentence. A correction assumes a troublesome feature is a mistake and provides an alternative. While spelling and grammar errors can be obvious, choices in style and usage can be much more challenging to diagnose. Experienced readers may know that a sentence doesn’t sound right, but may not have a vocabulary to explain why their correction would be preferred.

Focus on patterns of error, not individual mistakes: All writers make sentence-level errors. It is not necessary in all cases to identify the ‘cause’ of an error, nor is it wise to assume any particular error is evidence of some root cause or problem (like inattention, lack of knowledge, or second language intervention). As copy editors become rarer and the pace of publication cycles becomes faster, sentence-level errors emerge even in published writing.

Use a minimal marking strategy. When making a note of a sentence-level error, it is unwise to spend time correcting it. Multiple research studies (in 1990, 2004, and 2015) have shown that making a checkmark at the end of a line that includes an error should be enough to draw a student’s attention to the error and promotes self-correction (so long as you have announced what your checkmark means). Some students may have difficulty identifying some errors, but wholesale correction does not produce better writers. In the event that a student has error identification issues, a brief conference will often help.

If you know something is wrong, but aren’t sure what the error is called, respond as a reader and start a conversation. Drawing a wavy line beneath garbled sentences or making a margin comment of “I can’t understand you here,” will put the responsibility on the writer to find a way to clarify. Asking an open ended question can usually begin a conversation about the writer’s choices and lead to changes or revisions.

Turn common issues into teaching ideas. You will certainly see patterns and repeated issues in any set of submissions. Rather than repeating every comment for every student, consider consolidating your comments. This consolidated response could be delivered as a handout with an explanation, demonstration, or discussion in class.

Audio and video feedback

Research on audio and video feedback

Audio and video feedback are well-studied practices for responding to writing. While no single type of feedback is more effective in all cases, students report that they appreciate the level of detail and personalization that comes from audio and video feedback (McCarthy, 2015). In addition, students also perceive greater social presence from instructors using video feedback (Borup, West, Thomas, & Graham, 2015). While audio and video feedback are especially valuable in online and distance contexts, they can be a useful addition to any course context, as long as all students’ access needs are taken into account.

Recording audio or video feedback

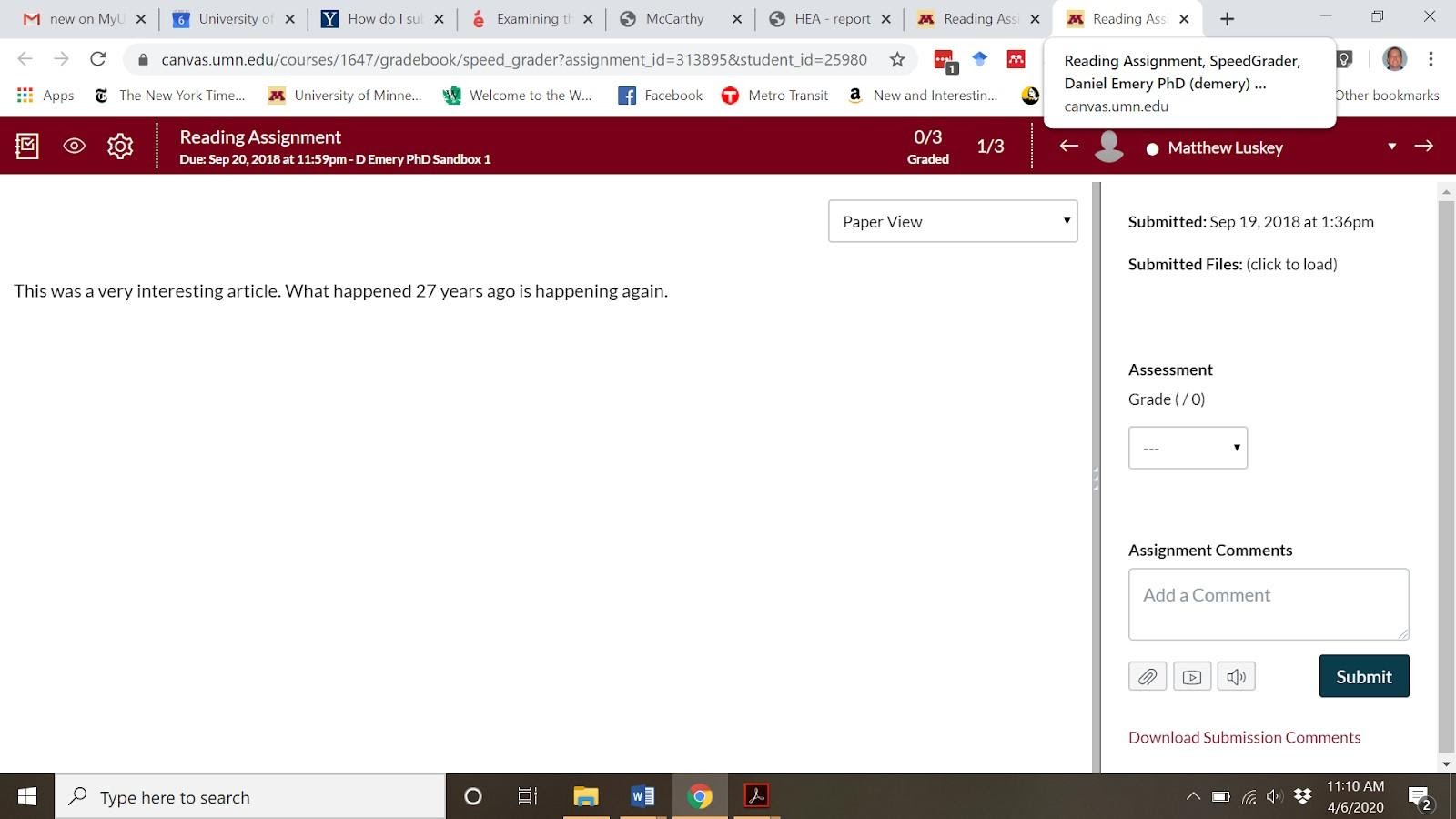

When instructors use the “Assignments” feature of Canvas to create student tasks and gradebook entries, the Speedgrader tool has built-in capability for recording brief audio and video feedback. Under the text box for the comment feature, three buttons provide options for attaching files and recording video and audio: (Image description: screenshot of the instructor view of a Canvas assignment web page. On the lower right, the instructor view includes a text box labeled “Assignment Comments,” with three buttons below, each with its own icon: a paperclip, a video icon, and an audio icon.)

Selecting the video or audio buttons will prompt Canvas to request access to camera and microphone options. After granting permission, an instructor can easily record feedback with the press of a button. The recording is available for preview, prompting the instructor to save the recorded comment or to start over to rerecord.

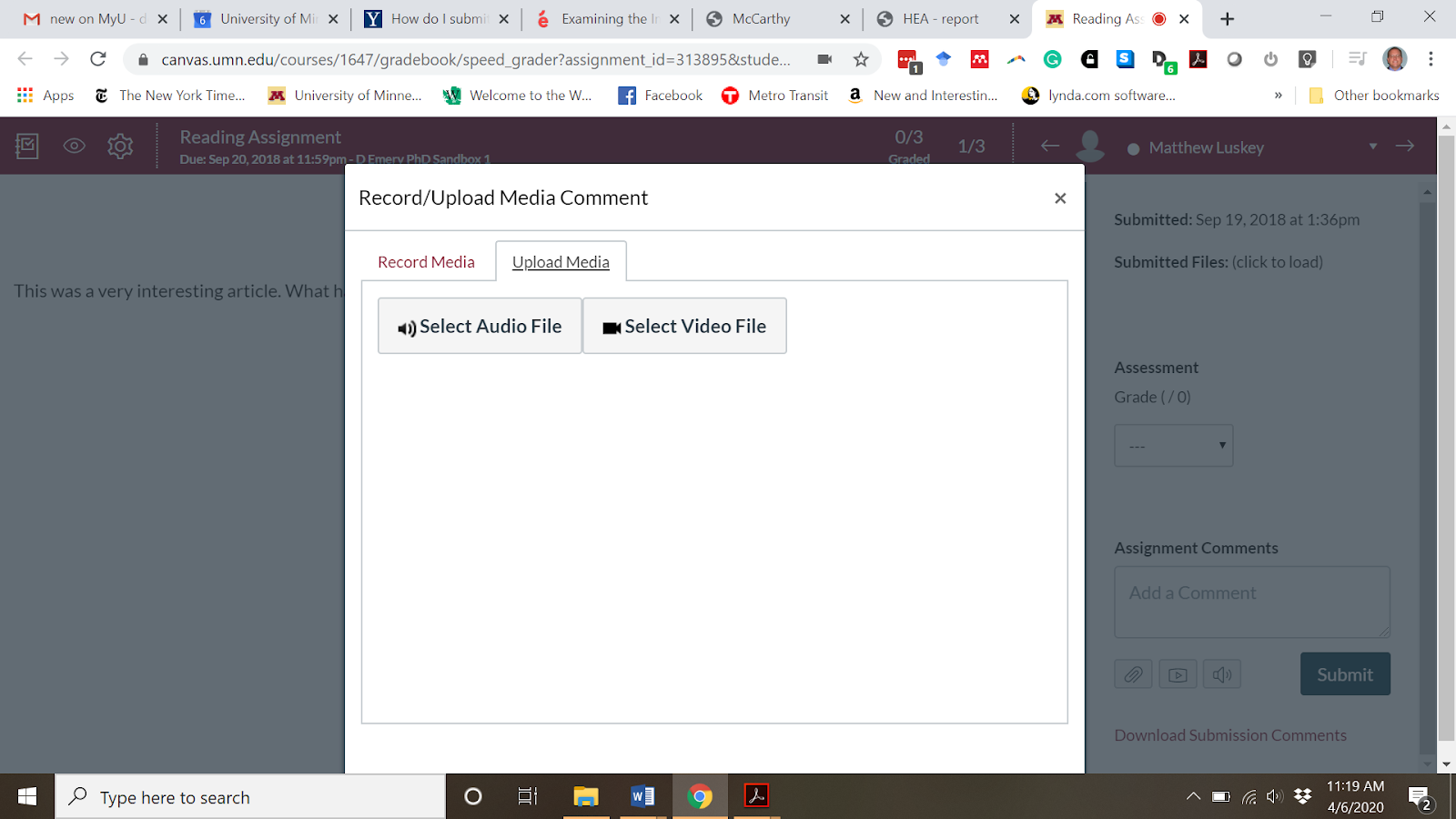

Canvas also affords the option to upload audio or video files using the same buttons. The second tab offers upload options and supports a variety of file types: (Image description: Canvas’s Record/Upload Media Comment window with two tabs. The first tab, “Record Media,” is not selected; the second tab, “Upload Media,” is selected and shows options labeled “Select Audio File” and “Select Video File”.)

Remember students’ access needs: Addressing accessibility is crucial for using audio and video feedback, both for students who receive accommodations for disabilities and for students who may have limited access to technology. As with any online instructional activity, some activities may need to be modified or changed to serve students equitably. Advice and assistance are available through the Accessible U website.