Finding the Right Words: Using Mind Mapping to Develop Research Topics

Co-written by Kate Peterson

For some students, the process of finding a research question or topic begins in their heads and ends when they locate research and resources that seem to address that question. Whether it is because they are newcomers to research or interested in selecting only an ‘original’ line of inquiry, students may not recognize that library searches can be opportunities for exploration and discovery rather than merely identifying resources to illustrate an already formed thesis. In this blog post, collaboratively written with Kate Peterson from University Libraries, we’ll profile a mind mapping strategy you can use with your students to generate more precise and focused research.

What makes finding a topic challenging?

Librarians who research the development of students’ information literacy note that while many aspects of seeking information are challenging, most students struggle at the very beginning. According to a retrospective analysis of library research, getting started — defining a topic, narrowing it down, and figuring out what is required — is most difficult for students conducting course research. Students’ choices are influenced by things like:

- what they think a “good” topic is (widely known or under-considered, heavily researched or unexplored, historical or contemporary)

- what they think they “should” be researching their expectations of the instructor

- the assignment guidelines and assessment criteria

- their past research experience (whether good, bad, or mediocre)

- the amount of time they have for this part of the project or the whole project

- the tendency to quickly switch topics if they aren’t finding what they are expecting (focused on efficiency)

- inexperience reading and evaluating research articles and journals

- their initial Google searches

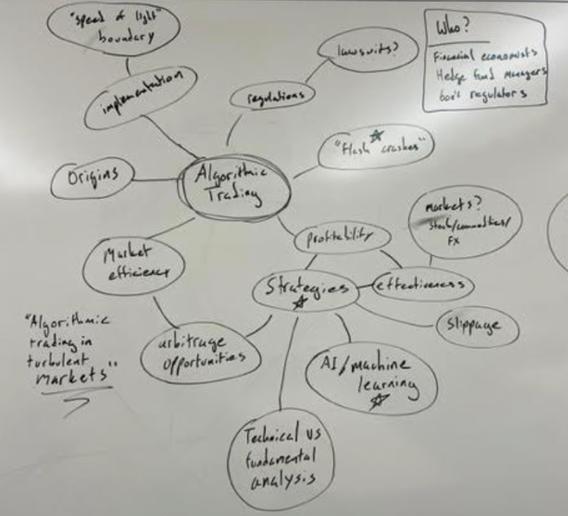

While course topics and readings are often the entry point for research projects, a mind mapping activity that centers the student’s interests or initial questions can yield more focused and relevant research. Mindmaps, or idea maps, are visual representations of ideas and topics. Branching from a central term, the mindmap asks students to identify other ideas, terms, or questions that may be related to their initial topics.

Generating mindmaps: A structured class activity

First, an instructor or librarian makes an “example” mindmap with the class, usually on a whiteboard.

The example could be a course topic, a current news topic, or something most students know about (e.g., TikTok, sleep and grades, video games). Or the instructor can ask small groups of students to generate a list of sub-topics and questions and then have these small groups report out to populate the map.

Second, students or groups make their own mind maps on their preliminary topics.

Students use whiteboards or paper (or tools like LucidChart or Miro) to make a mindmap on their own topic or possible topic. It can be made up of words, keywords, concepts, search terms, names, events, questions, things they know about the topic, things they don’t know about the topic, drawings, anything! Librarians who use this activity usually challenge students to make 15 bubbles in 4 minutes (a goal and timeframe help to encourage quick ideas)

Third, students share their initial map with a partner or group.

In this most critical step, instructors can ask students to turn to the person/group next to them and briefly share their topic and mind map— they can add more items to their mind map as they talk, too. Listeners can also give suggestions, but the focus is on providing the mapper room to explore and verbalize what they notice about their topic and associations. Be sure to ask students to snap a picture of their maps for later use.

Using what students have generated: Questions to ask of map makers

Where do you want to start research first?

Writers start too broadly with research, so the mind map can help students see how big a topic is and how many sub-topics or roads there are. One next step is to look at the branches of their mind map to narrow the direction they want to head first. Following branches could lead to a more focused topic or another set of branches and concepts to further restrict the focus and range of their subjects.

Who is researching and writing on your topic?

For many interdisciplinary topics, it can be hard to identify where to search -- so quickly asking students to write down (on the whiteboard) who they think might be doing research and writing on the topic is helpful -- e.g., doctors, teachers, lawyers, engineers, business professors, historians, psychology, communications studies, and so on. This information can help to identify a useful article database using our list of subjects.

Using these keywords, what are you finding?

After 10–15 minutes of searching using library databases or other search tools, ask students to pick one useful source. Have students write it on the board or read one aloud in class. It brings the activity full circle and also lets others in the class continue to get familiar with this academic publishing and a sense of some of the sources their classmates are finding (even on different topics).

Closing the loop: From map to the research question

Students may arrive in our classes with experience in writing from sources and engaging in attribution; for many, those features define research writing. They may need help understanding what research writing means in specific disciplinary contexts. In health sciences, developing a research question may focus on a PICOT question, while in communication studies, students may devise research questions to be answered with an argumentative thesis. Different mapping strategies might be more appropriate to your teaching context, including idea maps, concept maps, and argument maps.

Additional notes on mapping for researchers:

- Mindmaps can be used at many stages—the beginning, middle, and end of a project—to explore a new topic or fill research gaps.

- Maps can also take many forms, from free-flowing word clouds to linear or hierarchical structures of relationships.

- Mindmaps can also be used to take notes on readings (or lectures)

- Mindmaps can outline a paper or project (video, presentation, podcast, etc.)

- Mindmaps can be helpful to new researchers, to those new to a topic, or to those who have been working on a topic for decades.

Further Support

The University Libraries offer resources for course-integrated instruction with librarians. Additional information about this service and others can be found on the library’s Resources for Instructors page.

See the Teaching with Writing pages and our Teaching Resources for more good advice. Our WAC program hosts the popular Teaching with Writing event series. Each semester, this series offers free workshops and discussions. Visit us online and follow us on Twitter @UMNWriting. Contact us to schedule a phone, email, or face-to-face teaching consultation.

- Log in to post comments