Right Here, Right Now: Using Writing to Support Contemplative Practices

It’s November, and we are two-thirds of the way through the semester. Temperatures are dropping and anxieties are rising. Midterms have just finished, registration for Spring semester opens next week, and we have little more than a month of classes. Student Writing Support in the Center for Writing is averaging over 400 appointments a week and will maintain this frenetic pace through the semester. To top it off, daylight savings time has ended; our work days end in darkness. For many of us, it can feel, in John Keats’s words, as if “the sedge has withered from the lake, and no birds sing.” This is a time when energy levels are low and in need of renewal.

But how to slow down and focus amidst the late-semester pace and push? This month’s TWW post suggests ways to use writing to support contemplative practices that foster reflection and heightened awareness—practices that have been shown to reduce stress, increase attention and focus, and develop empathy and interpersonal connection.

What are Contemplative Practices?

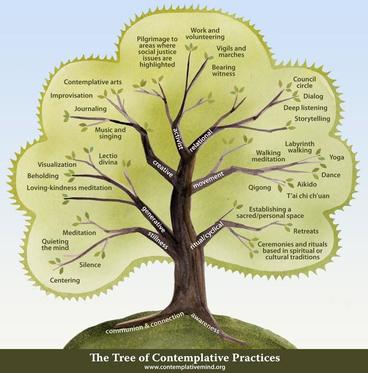

Academic approaches to teaching and learning often focus on measurable learning outcomes—products produced by students that demonstrate knowledge. Contemplative practices can certainly support these academic endeavors, but they are more attuned to the mental and emotional processes of learning than to specific products. As illustrated in The Tree from the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society, contemplative practices involve a variety of exercises, such as intentional breathing, guided meditation, beholding, slow reading, and deep listening. In the context of higher education, each of these introspective exercises can help faculty and students monitor their own teaching and learning by paying close attention to their thoughts and feelings in the present moment. Contemplative writing can support this holistic approach.

Contemplative Writing

Contemplative writing (aka mindful writing) often uses genres and activities familiar to classroom practices, such as journals, freewriting, and in-class responses. However, the self-reflective purpose and holistic perspective of contemplative writing may entail a shift for some students, especially when they are asked to contemplate their feelings and emotions in relation to course content. Here are three suggestions for using contemplative writing.

Suggestion 1: Focus on the First-Person Present

A good deal of academic writing prioritizes the third-person perspective because it conveys a detached and objective point of view. Contemplative writing is first-person. It is writing from the self and for the self. If you are providing a space for students to write in your class and you want them to engage in mindful reflection about their learning, provide them with prompts that are clearly self-directed: What matters here in your learning? Where are you now? What do you know now? What would you like guidance on? Who can support you and how? Along with providing such prompts, it’s helpful for instructors to signal that the writing is for the student and that any sharing of that writing is optional.

Example: Dr. Allison Brenneise, an instructor in Communication Studies, begins her class with a guided meditation and ends with a short contemplative writing activity: “If you speak today, see yourself doing well and having all the words flow through you the way you want them to; if you are the audience today, see yourself as a receptive listener, willing to engage new ideas, giving the types of nonverbal feedback to the speaker that you would like to receive or that will help them know if you understand.” Near the end of class, Brenneise returns to the opening meditation and poses a Question of the Day, which students respond to in writing. The question varies, but it always emphasizes the first-person and the present, such as: “What have you learned today that you did not know yesterday or this morning?”

Suggestion 2: Build Trust and Be Flexible

As Daniel Barbezat and Mirabai Bush explain, contemplative practices operate well when students trust their teachers, and “trust deepens when students understand why they are being asked to do something, especially if it is outside their comfort zone” (72). Transparency about the use of contemplative writing is key, along with an awareness and sensitivity to ways that contemplative writing might conjure up particular religious or cultural associations. Writing activities that ask students to first maintain a period of silence or to close their eyes might inadvertently produce tension and resentment, especially if students come from backgrounds that have felt traditionally silenced by formal education, or who have suffered trauma and do not feel safe closing their eyes in a group. Offering students opportunities to opt-out or alternate ways to engage (close your eyes or relax and focus softly on an object) helps build an environment of trust. “Being attentive and aware of the contexts that students bring with them into the classroom,” Barbezat and Bush maintain, “allows us to foster safer, more inclusive environments for all students” (74).

Example: Dr. Brenneise has consciously integrated contemplative writing into her course. Students are frequently reminded of the purpose behind the practice, and they are often asked to link the daily writing to specific course learning objectives identified in the syllabus. In a similar fashion, Barbezat, a professor of Economics at Amherst College, introduces contemplative practices on the first day of class, asking students to look over the syllabus and imagine themselves throughout the semester, “writing down what percentage of the reading they want to do over the semester and how much they are willing to do” (72). Students are then invited to consider what the differences in their desires and their commitments about course reading might mean.

Suggestion 3: Encourage Contemplative Writing Beyond the Classroom

As documented by Ambrose et al. and other educational research, when “students carefully monitor their progress and explain to themselves what they are learning, they have greater learning gains.” (For more information, see Chapter 7, “How Do Students Become Self-Directed Learners?” in How Learning Works). Providing opportunities in class for students to contemplate on their present learning—including their emotional states—can often lead to ongoing reflection. You can encourage students to extend their reflections by carrying a small notebook or using their phones to capture ideas—sentences, images, graphs, and figures—they want to reflect on. Doing so might even lead them to moments of joy, amidst the cold and the clamor of the semester.

Example: A University of Minnesota student majoring in Art and History uses the “Notes” app on their phone to write down sentences they want to mull over. In the student’s words, “It is a joy to find that rare, often obscure passing word that so accurately encompasses how I feel about something.”

Where are you?

Do you use contemplative writing in your courses? Do you engage in contemplative writing yourself? If so and you are comfortable sharing, we invite you to use the comment function below. Are you interested in finding out more? Feel free to schedule a consultation. You can also read more about reflective practices at the Bakken Center for Spirituality and Healing. If you would like to integrate mindful writing and other contemplative practices into a specific course next semester, we encourage you to register for the Teaching with Writing Winter Workshop on January 15, 2020. Additional details are provided below.

Further Support

See the Teaching with Writing pages on the Center for Writing website for teaching resources. As many of you know, our WAC program also hosts the popular Teaching with Writing event series. This year, in addition to fall and spring events, we are pleased to feature a Teaching with Writing Winter Workshop on January 15, 2020. Faculty, graduate instructors and teaching assistants are encouraged to register for workshops and consultations focused on course and assignment planning, effective feedback strategies, and efficient and inclusive grading practices. Visit us online and follow us on Twitter @UMNWriting. To schedule a phone, email, or face-to-face teaching consultation, click here.

- Log in to post comments

Comment

I incorporate two Reflection…

I incorporate two Reflection assignments into the lab course I teach, where students are doing semester-long group research projects. I think these assignments help them think about how the research process is going, and recognize their progress toward the end of the semester. Also, it's been surprisingly helpful to ask (in week 5 of the semester) what they've struggled with most so far: we don't always see the challenges students are experiencing, but sometimes we can help address them once we know.

It's great to read about…

It's great to read about reflective writing in your biology courses, Catherine. As you point out, there is so much students and their instructors can learn from reflections throughout the term. Thanks for sharing!